My grandma read my previous post about the plants I procured from her, and she e-mailed with corrections for my accounts about the roses I inherited:

You have a healthy looking garden. Bravo !!

It is the Graeber rose. Gus Graeber from Stevensville Mich gave it to Carl. Gus is a gardner par excellence. He grew up on a fruit farm in the St. Joseph area of Micxh. He was also a first class orchid grower.

And the yellow rose came from the farm yard of your great great grandmother. She died before I was born so I never knew her. My aunt Mary (the Yordy's) were living on the place when I dug up the rose for our garden when I was in high school in the late 1930's.

Monday, May 30, 2005

Sunday, May 29, 2005

airport

My grandma read my previous post about the plants I procured from her, and she e-mailed with corrections for my accounts about the roses I inherited:

You have a healthy looking garden. Bravo !!

It is the Graeber rose. Gus Graeber from Stevensville Mich gave it to Carl. Gus is a gardner par excellence. He grew up on a fruit farm in the St. Joseph area of Micxh. He was also a first class orchid grower.

And the yellow rose came from the farm yard of your great great grandmother. She died before I was born so I never knew her. My aunt Mary (the Yordy's) were living on the place when I dug up the rose for our garden when I was in high school in the late 1930's.

You have a healthy looking garden. Bravo !!

It is the Graeber rose. Gus Graeber from Stevensville Mich gave it to Carl. Gus is a gardner par excellence. He grew up on a fruit farm in the St. Joseph area of Micxh. He was also a first class orchid grower.

And the yellow rose came from the farm yard of your great great grandmother. She died before I was born so I never knew her. My aunt Mary (the Yordy's) were living on the place when I dug up the rose for our garden when I was in high school in the late 1930's.

Wednesday, May 25, 2005

fast

Or should I say slow?

I hereby declare, on this 28th day of May, 2005, that I will abstain the from overpowering bilge of information offered up on these here Internets. My NewsFire has been purged of all news sites. I will not watch TV news either, nor read any newspapers or magazines unless I'm directed there by one of my trusted sources -- my friends and family, and these dozen or so cherished blogs:

about contemporary lit

angryblackbitch

backstory

bitchbook (& assorted mutterings)

cup o joel

death's door

dreadnaught

house of e

me, myself + infrastructure

mtoast

pomegranate pretty

shelby

thanks for not being a zombie

tony's kansas city

The following blogs are on the cusp; I'm not sure if they'll make the final cut:

the revealer

meditation blog

So, if your blog is on this list, and you're reading this, let me know if anything really important happens. I mean in the so-called real world. Obviously the stuff you folks write about all the time is extremely important, otherwise I wouldn't be taking it with me to my virtual island.

Theory behind this: I want to experiment with perceiving the world only through friends and distant admirees who, for the most part, are describing it for no other reason that it needs describing. By them. Money be damned.

More than that, I feel beaten down by information. Or addicted to it. Several times a day I reach for the laptop out of impulse and spend valuable time sifting through stories and blog entries. It gets in the way of bigger things I want to accomplish, books on my list, work I want to do, quality time with my woman, friends, family, and my dogs and cats. And the payoff is so small, except, I find, with these blogs I've listed here. All the stories moosh together, few stick with me in any meaningful way.

It'll be interesting to see if I can pull it off.

If so, my fast will break right around Labor Day weekend. (I will read books, of course; sounds like a good summer to me!)

I hereby declare, on this 28th day of May, 2005, that I will abstain the from overpowering bilge of information offered up on these here Internets. My NewsFire has been purged of all news sites. I will not watch TV news either, nor read any newspapers or magazines unless I'm directed there by one of my trusted sources -- my friends and family, and these dozen or so cherished blogs:

about contemporary lit

angryblackbitch

backstory

bitchbook (& assorted mutterings)

cup o joel

death's door

dreadnaught

house of e

me, myself + infrastructure

mtoast

pomegranate pretty

shelby

thanks for not being a zombie

tony's kansas city

The following blogs are on the cusp; I'm not sure if they'll make the final cut:

the revealer

meditation blog

So, if your blog is on this list, and you're reading this, let me know if anything really important happens. I mean in the so-called real world. Obviously the stuff you folks write about all the time is extremely important, otherwise I wouldn't be taking it with me to my virtual island.

Theory behind this: I want to experiment with perceiving the world only through friends and distant admirees who, for the most part, are describing it for no other reason that it needs describing. By them. Money be damned.

More than that, I feel beaten down by information. Or addicted to it. Several times a day I reach for the laptop out of impulse and spend valuable time sifting through stories and blog entries. It gets in the way of bigger things I want to accomplish, books on my list, work I want to do, quality time with my woman, friends, family, and my dogs and cats. And the payoff is so small, except, I find, with these blogs I've listed here. All the stories moosh together, few stick with me in any meaningful way.

It'll be interesting to see if I can pull it off.

If so, my fast will break right around Labor Day weekend. (I will read books, of course; sounds like a good summer to me!)

Monday, May 23, 2005

more letters

From a letter to Bill Kambs, May 13, 1976:

Be dilligent, let the life of Jesus Christ take on a tangible form. The Lord said, "And I will give you intercessory power and you shall see signs, miracles and wonders." What are we going to do? Do you realize that when Jesus called people in the Gospels they were called to a practical tangible action, a drastically radical action? "Sell all you have and give it to the poor," he said to the rich man. The man could have foolishly said, "But giving the poor money isn't really going to meet their need." But he would have forgotten that he didn't ask the Lord how to help the poor. He asked the Lord how to get eternal life. This is probably my natural reaction. I ask the question what should I do? He tells me, then I get into relating to the results and forget that his command really related to the question, "What should I do?"

From a letter to "Brother Frank, Jackie and kids," May 24, 1976:

The Lord is good. Praise his name. I think the Lord began to clarify a principle for me as I read Francis Schaeffer's book, True Spirituality. He was talking about the dilemma of being human. We are made in God's image yet we die like animals. We can't say that we're like animals because we aren't. So we can't live on a lower level and be happy, but we can't live on a higher level either because even though we have a personality capable of moral judgement like God we are mortal like animals and finite where God is infinite. He has no limitations nor does He die. But we are stuck in the middle. This seems to be a principle God wants me to understand. For instance as a 20 year old, we were something, not a child, not a man. We were something, but not what we were going to be. Not a sheep, not a shepherd. We keep on going yet the grass is always greener ahead. We are sort of in the middle of things at all times and to learn to be content in that middle place and to function there and do the things that are for that period without feeling bad because we haven't reached where we can see and without slacking off and taking it easy on a lower level.

I bristle at some of what he's said here -- the God's image part, the implied seperation from nature, the certainty oof the hierarchies -- but I'm touched by this idea of flux he's grasping at.

Be dilligent, let the life of Jesus Christ take on a tangible form. The Lord said, "And I will give you intercessory power and you shall see signs, miracles and wonders." What are we going to do? Do you realize that when Jesus called people in the Gospels they were called to a practical tangible action, a drastically radical action? "Sell all you have and give it to the poor," he said to the rich man. The man could have foolishly said, "But giving the poor money isn't really going to meet their need." But he would have forgotten that he didn't ask the Lord how to help the poor. He asked the Lord how to get eternal life. This is probably my natural reaction. I ask the question what should I do? He tells me, then I get into relating to the results and forget that his command really related to the question, "What should I do?"

From a letter to "Brother Frank, Jackie and kids," May 24, 1976:

The Lord is good. Praise his name. I think the Lord began to clarify a principle for me as I read Francis Schaeffer's book, True Spirituality. He was talking about the dilemma of being human. We are made in God's image yet we die like animals. We can't say that we're like animals because we aren't. So we can't live on a lower level and be happy, but we can't live on a higher level either because even though we have a personality capable of moral judgement like God we are mortal like animals and finite where God is infinite. He has no limitations nor does He die. But we are stuck in the middle. This seems to be a principle God wants me to understand. For instance as a 20 year old, we were something, not a child, not a man. We were something, but not what we were going to be. Not a sheep, not a shepherd. We keep on going yet the grass is always greener ahead. We are sort of in the middle of things at all times and to learn to be content in that middle place and to function there and do the things that are for that period without feeling bad because we haven't reached where we can see and without slacking off and taking it easy on a lower level.

I bristle at some of what he's said here -- the God's image part, the implied seperation from nature, the certainty oof the hierarchies -- but I'm touched by this idea of flux he's grasping at.

weeds

I've been pulling a lot of weeds here in Indiana. Pulled a bunch at my grandma's house, and my aunt Lynn's, my cousin Cortney's, Uncle Evan's. Grandpa wants me to come over and pull some for him too, though I don't know if I'll have time.

I like it. I find myself pulling weeds evenn where I have no business doing so, like when I'm walking down the sidewalk or when I'm visiting someone's house. I'll just lean over and pluck one or two out of the ground.

It's not quite as tricky as bowling, but there's still an art to it. You gotta be calm and gentle, grab it at just the right spot, give the thing a gentle shake while you're pulling to relax its hold on the dirt.

There's so many damn weeds. They grow a lot faster than anything we want to grow. Back home in KC, weeding is part of my morning routine. I call it weeditation. First thing in the morning, I do a spin around the garden beds, and there are just as many weeds to pull as there were the day before.

I sometimes wonder what the world would look like if I wasn't here to weed it. I know what my yard would look like. It would look like crap.

And I'm like, What does that say about nature? Which is a pretty stupid question. Nature looks best when we're not around. I once toured a hippy ranch in central Kansas, where the main hippy cowboy guy told me that the surface of Kansas prairie used to be this dense living organism that was so perfectly balanced and delicate that the minute a settler stabbed a plow into it it was destroyed. I guess that's the same way it is up in the Arctic Wildlife Refuge, where they wanna tear it up for oil and Ted Stevens.

So what, then, are weeds? Are they just like precursors to the natural state of things, or are they these weird biproducts of our arrogant intrusion, plants made heartier and more resilient by our efforts and desires to get rid of them.

Gardening is such a trip. It's like controlling nature, like taking what would naturally just array the world however it sees fit in a way that we see fit, which is in a more compartmentalized way, in beds and such. Weeding reminds me of my years in AA, when I made numerous "personal inventories," the universally dreaded chore of recovering alcoholics to list and under our shortcomings. Sort of a Duh! metaphor.

Weeds make me all the more certain that we're not made in God's image, that we're actually contrary to it. In a lot of ways, anyway. And I think this actually makes us kind of neat, certainly privileged, because of all the beasts of the land, we have the most advanced abilities to create, or at least reorder, which is creation in a way, at very least it's a dance. But it's horrifying too, this apartness from nature we live in, the agony of our self-appointed God's imageness. Because once you start ordering things, once you decide that hibiscus plants will look better in that spot by the maple tree than whatever plant naturally might sprout up there, then you're hooked for life. You'll never stop stoping to yank up those weeds.

I guess this makes about as much sense as a TV on a camping trip. Funny, I started off wanting to right something about the corny symbolism of pulling weeds on a visit to family, especially a painfully introspective one like this. But what I really want to know is what's the deal with weeds? What does their history say about ours? Maybe I'll look into it one of these days.

I like it. I find myself pulling weeds evenn where I have no business doing so, like when I'm walking down the sidewalk or when I'm visiting someone's house. I'll just lean over and pluck one or two out of the ground.

It's not quite as tricky as bowling, but there's still an art to it. You gotta be calm and gentle, grab it at just the right spot, give the thing a gentle shake while you're pulling to relax its hold on the dirt.

There's so many damn weeds. They grow a lot faster than anything we want to grow. Back home in KC, weeding is part of my morning routine. I call it weeditation. First thing in the morning, I do a spin around the garden beds, and there are just as many weeds to pull as there were the day before.

I sometimes wonder what the world would look like if I wasn't here to weed it. I know what my yard would look like. It would look like crap.

And I'm like, What does that say about nature? Which is a pretty stupid question. Nature looks best when we're not around. I once toured a hippy ranch in central Kansas, where the main hippy cowboy guy told me that the surface of Kansas prairie used to be this dense living organism that was so perfectly balanced and delicate that the minute a settler stabbed a plow into it it was destroyed. I guess that's the same way it is up in the Arctic Wildlife Refuge, where they wanna tear it up for oil and Ted Stevens.

So what, then, are weeds? Are they just like precursors to the natural state of things, or are they these weird biproducts of our arrogant intrusion, plants made heartier and more resilient by our efforts and desires to get rid of them.

Gardening is such a trip. It's like controlling nature, like taking what would naturally just array the world however it sees fit in a way that we see fit, which is in a more compartmentalized way, in beds and such. Weeding reminds me of my years in AA, when I made numerous "personal inventories," the universally dreaded chore of recovering alcoholics to list and under our shortcomings. Sort of a Duh! metaphor.

Weeds make me all the more certain that we're not made in God's image, that we're actually contrary to it. In a lot of ways, anyway. And I think this actually makes us kind of neat, certainly privileged, because of all the beasts of the land, we have the most advanced abilities to create, or at least reorder, which is creation in a way, at very least it's a dance. But it's horrifying too, this apartness from nature we live in, the agony of our self-appointed God's imageness. Because once you start ordering things, once you decide that hibiscus plants will look better in that spot by the maple tree than whatever plant naturally might sprout up there, then you're hooked for life. You'll never stop stoping to yank up those weeds.

I guess this makes about as much sense as a TV on a camping trip. Funny, I started off wanting to right something about the corny symbolism of pulling weeds on a visit to family, especially a painfully introspective one like this. But what I really want to know is what's the deal with weeds? What does their history say about ours? Maybe I'll look into it one of these days.

Sunday, May 22, 2005

church

This morning I went to Zion Chapel. It was the church by father attended when he was born again in the early 1970s. It can be said that my father was part of the "Jesus People" movement; he was a young guy who'd gotten lost on drugs and found salvation in charismatic, fundamentalist Christianity. He died in 1976, when I was eight years old, in an accident while building a church in Mexico.

I was apprehensive about my visit to this church all these years later. My early experiences with my father's faith have marked me in ways I'm still struggling to understand. What I do know is that I didn't much like the way he worshiped nor the frameworkk of his faith, and, I must admit, I didn't much like him either because of it. I found his faith to be frightening. I was spooked out by his and his friend's speaking in tongues and embarrased by the way they clapped and shook tamborines and closed their eyes and raised their hands upward as if they were being sucked up into a warm shaft of light. Most of all I disliked -- no, rejected -- their concept of God and Christianity, which I interpreted like this: Being Christian means pretending like you're perfect. I was only four or five or six at the time, but I somehow knew that I wasn't perfect and that I didn't want to be (especially if being perfect meant never again listening to Top 40 radio).

Now I'm 37 and I come back to the church with new baggage. I've been born again a couple of times, baptized a couple of times, but I still feel almost totally disconnected from Christianity. For most of my life I have not been involved with a church. Recently, I began attending a quaker meeting, but iit's been months since I've gone.

I arrived at Zion Chapel a bit early. It has a large octagonal sanctuary with a hardwood ceiling that vaults up toward a point in the middle. There's a stage on one end and perhaps 500 chairs lined up facing it. They're nice chairs, with comfortable padding and green upholstery. An american flag hung to the left of the stage. An eight piece band was playing instrumentals. At one point they broke into what sounded like "Sweet Home Alabama."

There were people there of pretty much all ages, though most appeared to be under 40, and they were all white.

The service began with a long set of songs by the band. The band was very good. They reminded me of the Counting Crows. During a song about prayer, the pastor invited people to come up to the microphone and share a miracle they'd witnessed the previous week. One woman said that after praying her arthritis pain disappeared. Another said that prayer has helped her granson to see better and to learn how to read.

I was uncomfortable from the start. This is due in no small part to my own prejudices and ideologies. For one, I have this thing about churches being big beautiful buildings. I know that thiis sounds insane, but I think it's hipocritical to worship Jesus in an expensive, austentatious building.

As ilistened to the songs, I grew more and more squirmy, cranky and judgmental. The songs made it all sound so easy -- just pray and believe and all these vague, wonderful things will happen: mountains will move, sunlight will burst through clouds, we'll all be free. Then I got more iritiable during the miracle part, as I said, and then got, I don't know, bitter when I heard the singer say, to the beat, "There are so many out there who are lost."

Finally, I got up and left. II just couldn't stand it.

One of the reasons why I don't attend church is that I often feel that they're Satanic, that they dispense the elixir of false prophets. And that's what I felt here (though I must also concede that there are no doubt very deep, personal history forces at play here).

I know I'm treading dangerous ground here. I'm trying to express this as simply and honestly as possible.

At chruches like this, I sense that there's too much focus on the Good News, the life offered in the Gospel, and not enough on the death that's critical to attaining this freedom and salvation. The simple songs these folks sang all seemed to be saying: We've got it! We pray. We believe. And, for that, we are free.

But this overlooks what I see as the fundamental sin we face as American believers, and that is that we're American. I don't know how else to put it. We're on the so-called winning side of global injustice.

I know I'm sounding like a freak here. But it's so clear to me. If we just look at it terms of consumption. Most economic data indicates that we consume the world's resources at a rate that's absurdly higher than almost every other culture on earth. And we also are big time consumers of the lives of fellow human beings, in the form of below-subsistance wages or in the form of actual lives taken away in pursuit of American or Western hegemony. And I'm counting here not only the lives and resources that are being consumed right now, but also those which have been consumed by our history, which, in the not so distant past was cruel beyoond anything we could possibly accept now.

So when I go to church, I actually want to be challenged to die. I need to be challneged to die. And when I'm not challenged to die, I get pissed off, because what I see is other privileged people like myself affirming their privilege, ignoring the suffering upon which it is borne. As Americans, we have this sort of affirmation at every turn, 24-7. But when I read something like the Sermon on the Mount, I see really, really tough words that seriously indict so much of the way we live as Americans. And at very least, it seems, a portion of any worship of Jesus, of getting in line with the example and way his life ostensibly offered ought to have some serious smack time.

I don't think I'm getting out the thought (or thoughts) I'm working through.

Perhaps it's like this: As Michael Eric Dyson said recently on Book TV, "Context is critical." And I wonder if in the context of white America the Good News can really be taken on faith. My sense is that it's really being twisted into propaganda. I more than wonder, I believe this to be so, whether or not it actually is. And believing this, I can't help but see such things as evil.

But if context really is critical, then I have to go all the way. And I have to at least superficially concede my own part in this assessment, which is very likely 100 percent. I walked out of this church that my father helped build so many years ago based on a very quick, categorizational, and subsequently prejudicial, assessment of it.

And my treatment of that here is superficial not because I think this part of it is minor but because I know that it is the most important part of the equation, that it's borne on my own shortcomings, my own anti-Christ-ness. And in this fact is the need for my own death (metaphorical, of course -- I ain't suicidal, so don't worry), which is damn scary to face. Like, I'm probably more guilty of false-prophetism than they are, being a journalist and, as such, inherently egomaniacal and deeply insecure.

So...

Um...

Big thoughts beget rambling shock, at least on first draft. Which is why this blog is subtitled "dirty beginnings."

I was apprehensive about my visit to this church all these years later. My early experiences with my father's faith have marked me in ways I'm still struggling to understand. What I do know is that I didn't much like the way he worshiped nor the frameworkk of his faith, and, I must admit, I didn't much like him either because of it. I found his faith to be frightening. I was spooked out by his and his friend's speaking in tongues and embarrased by the way they clapped and shook tamborines and closed their eyes and raised their hands upward as if they were being sucked up into a warm shaft of light. Most of all I disliked -- no, rejected -- their concept of God and Christianity, which I interpreted like this: Being Christian means pretending like you're perfect. I was only four or five or six at the time, but I somehow knew that I wasn't perfect and that I didn't want to be (especially if being perfect meant never again listening to Top 40 radio).

Now I'm 37 and I come back to the church with new baggage. I've been born again a couple of times, baptized a couple of times, but I still feel almost totally disconnected from Christianity. For most of my life I have not been involved with a church. Recently, I began attending a quaker meeting, but iit's been months since I've gone.

I arrived at Zion Chapel a bit early. It has a large octagonal sanctuary with a hardwood ceiling that vaults up toward a point in the middle. There's a stage on one end and perhaps 500 chairs lined up facing it. They're nice chairs, with comfortable padding and green upholstery. An american flag hung to the left of the stage. An eight piece band was playing instrumentals. At one point they broke into what sounded like "Sweet Home Alabama."

There were people there of pretty much all ages, though most appeared to be under 40, and they were all white.

The service began with a long set of songs by the band. The band was very good. They reminded me of the Counting Crows. During a song about prayer, the pastor invited people to come up to the microphone and share a miracle they'd witnessed the previous week. One woman said that after praying her arthritis pain disappeared. Another said that prayer has helped her granson to see better and to learn how to read.

I was uncomfortable from the start. This is due in no small part to my own prejudices and ideologies. For one, I have this thing about churches being big beautiful buildings. I know that thiis sounds insane, but I think it's hipocritical to worship Jesus in an expensive, austentatious building.

As ilistened to the songs, I grew more and more squirmy, cranky and judgmental. The songs made it all sound so easy -- just pray and believe and all these vague, wonderful things will happen: mountains will move, sunlight will burst through clouds, we'll all be free. Then I got more iritiable during the miracle part, as I said, and then got, I don't know, bitter when I heard the singer say, to the beat, "There are so many out there who are lost."

Finally, I got up and left. II just couldn't stand it.

One of the reasons why I don't attend church is that I often feel that they're Satanic, that they dispense the elixir of false prophets. And that's what I felt here (though I must also concede that there are no doubt very deep, personal history forces at play here).

I know I'm treading dangerous ground here. I'm trying to express this as simply and honestly as possible.

At chruches like this, I sense that there's too much focus on the Good News, the life offered in the Gospel, and not enough on the death that's critical to attaining this freedom and salvation. The simple songs these folks sang all seemed to be saying: We've got it! We pray. We believe. And, for that, we are free.

But this overlooks what I see as the fundamental sin we face as American believers, and that is that we're American. I don't know how else to put it. We're on the so-called winning side of global injustice.

I know I'm sounding like a freak here. But it's so clear to me. If we just look at it terms of consumption. Most economic data indicates that we consume the world's resources at a rate that's absurdly higher than almost every other culture on earth. And we also are big time consumers of the lives of fellow human beings, in the form of below-subsistance wages or in the form of actual lives taken away in pursuit of American or Western hegemony. And I'm counting here not only the lives and resources that are being consumed right now, but also those which have been consumed by our history, which, in the not so distant past was cruel beyoond anything we could possibly accept now.

So when I go to church, I actually want to be challenged to die. I need to be challneged to die. And when I'm not challenged to die, I get pissed off, because what I see is other privileged people like myself affirming their privilege, ignoring the suffering upon which it is borne. As Americans, we have this sort of affirmation at every turn, 24-7. But when I read something like the Sermon on the Mount, I see really, really tough words that seriously indict so much of the way we live as Americans. And at very least, it seems, a portion of any worship of Jesus, of getting in line with the example and way his life ostensibly offered ought to have some serious smack time.

I don't think I'm getting out the thought (or thoughts) I'm working through.

Perhaps it's like this: As Michael Eric Dyson said recently on Book TV, "Context is critical." And I wonder if in the context of white America the Good News can really be taken on faith. My sense is that it's really being twisted into propaganda. I more than wonder, I believe this to be so, whether or not it actually is. And believing this, I can't help but see such things as evil.

But if context really is critical, then I have to go all the way. And I have to at least superficially concede my own part in this assessment, which is very likely 100 percent. I walked out of this church that my father helped build so many years ago based on a very quick, categorizational, and subsequently prejudicial, assessment of it.

And my treatment of that here is superficial not because I think this part of it is minor but because I know that it is the most important part of the equation, that it's borne on my own shortcomings, my own anti-Christ-ness. And in this fact is the need for my own death (metaphorical, of course -- I ain't suicidal, so don't worry), which is damn scary to face. Like, I'm probably more guilty of false-prophetism than they are, being a journalist and, as such, inherently egomaniacal and deeply insecure.

So...

Um...

Big thoughts beget rambling shock, at least on first draft. Which is why this blog is subtitled "dirty beginnings."

legacy

This was what i read at my grandfather's funeral:

The day after my grandpa died, I went with my grandma, uncle and cousin to buy a rosemary plant Grandpa had planned to buy. He'd had trouble growing rosemary. Days before he passed away he told Grandma, "This time we're gonna do it right."

This surprised me, as it would anyone who has visited my grandpa's corner of the world. When he moved to 125 Hollywood Avenue in Elkhart, Indiana, in 1954, it was a barren horse pasture. By the time I came along in 1968, it had become a lush alcove of flowers and towering trees, a favored spot for birds. It's a wild place, ever changing, full of nooks and curves. Grandpa shaped his garden with subtle strokes so as not to upstage God.

I couldn't imagine such a master gardener fretting over a common herb, but Grandma could. During their 60 years together, she had comforted him when he questioned his life's worth. "He would have considered himself a failure," she told me when I was back home for his funeral, in April. His self-doubt was most acute, she said, after my father passed away. He wondered where he had gone wrong; if he had given his oldest son too little care, or too much.

This surprised me too, and I wondered if my grandpa knew he was a hero to me. Not only for the ink he put in my veins (he was a newsman; a picture of him in a bow tie, with a pen poised above a piece of copy, hangs above the desk where I write), but because of the way he cared for me as I grew. He could be prickly, like when I was a teenager and he suddenly barked, "You're not innocent anymore!" Or when he mailed me a copy of one of my stories covered with red editing marks. He once yelled at his wife: "I'm humbler than you!" More often he was gentle. He had a terrific, infectuous laugh. He seemed to understand that nature would run its course no matter what he did. The world was never as peaceful and fair as he wanted it to be. It was a harsh climate in which to raise a family. But he led by example, and we all turned out ok. Even now, after all my moving around, and my distance from the place where I was born, I still look on my grandpa's two-acre plot in northern Indiana as my base. It's the place I go during my occasional visits to meditation, when I'm told to find my quiet, safe place.

The woman at the nursery wouldn't let us pay for the rosemary plant. She remembered my grandpa, as do scores of people I'll never know. On the drive home, Grandma told us that Grandpa had planned to go easy on the plant. Give it a little less water, perhaps. Let it do as God intends.

letters

When my grandparents traveled to Mexico for my father's funeral, they found in his room a stack of letters. He had used to ditto sheets to make copies of every letter he wrote, including ones to me. He had taken numerous trips to Mexico and Central America as part of his missionary work, but it was only in the last one that he took on archiving as a project. I am reading them now. I've read these letters before, perhaps ten years ago, but the experience wasn't as emotionally charged as it is now. The letters are stirring feelings on a number of different levels.

The most obvious feelings are the least immediate, that is the notion that these letters suggest a loss, a relationship I was unable to have with my father. We were both very young when he died -- he 27, me eight -- so there was a lot of unfinished business. As I've said elsewhere in this blog I didn't much like mmy dad. His faith scared me. But I am now just a few pages into this collection of letters, which span the time from late April 1976 when he first arrived in Minatitlan, Vera Cruz, Mexico until his death in October of that year, that he was undergoing a tremendous change which I have no doubt would have laid a foundation for reconciliation between the two of us.

But that's the least of it. A deeper pain is journalistic in nature. I feel that dread one feels when tackling a big, difficult but important and exciting story. The pain is more accute here because I am attached to it at the onset. But more signiificantly because it is shapping up to be a project unlike any I've ever taken on. So much of the story telling will be what I bring to it, and less what the story brings to itself, as is the case with most journalism. The structure is far froom obvious, and I tend to agonize when I don't have a fairly clear vision of where I'm going at the commencement.

Deepest pain of all comes in the aspect of discovery that is bound in this project, that I am not only going to unearth a story but that I am going to find aspects of myself, ugly ones, and that the project itself is a vehicle for self-discovery and change. All journalism projects are this way to a degree, but obviously this is a higher notch. Especially because this deals with issues of faith, spiritually and a sense of purpose in life and family and nation. I am at a stage of intense spiritual transformation, due to a number of factors I could name here but which I fear would be redundant and self serving. The main point is that I'm reading a historical record of the process of a spiritual transformation in a young man who was a lot like me, from whom I come, and in this reading come very difficult challenges to my own ways of being and assumptions and so on.

This, from a letter to Nan and Jim dated Friday, May 6, 1976, struck me:

I read this and regretted the post I wrote yesterday about Zion Chapel. I regretted my reaction to the service, my walking out and hoofing back to town on a country road. I regret too my propensity to criticize and preach. Over the last year it seems I've been apologizing a lot over outbursts of hot-headedness and self-riighteousnness.

Also, it's obvous here how simiilar I am to my father. He's clearly alluding to past conflicts he's had with his church, his judgement of how they choose to worship. I will probably learn more about the specifics of these co\onflicts in the coming years. But foo\r now I can see that if my dad had not died there would have been a moment, or moments of reconciliation where he would have realized how overzealous he was in his faith and how it really frightened me as a young child and messed up my own relationship with and understanding of God for many years to come.

This is a letter he wrote to me three days later:

I cavalierly say that I didn't like my dad, but I really loved him. I especially loved his inate sense of the surreal, his childlike wonderment at the absurdity of the world. This letter touches me. I can almost remember feeling tickled when I read it, or my grandma read it to me, with the image of the pig just waltzing in. It's great writing, really; so simple and clean that it's downright subversive. It was addressed to a middle-class kid in the Midwest, who assumes that things like solid roofs and floors and straight walls are the norm for the entire world. To learn that there is something different actually made the priviliged norms of my world seem absurd.

I will share more by and by

The most obvious feelings are the least immediate, that is the notion that these letters suggest a loss, a relationship I was unable to have with my father. We were both very young when he died -- he 27, me eight -- so there was a lot of unfinished business. As I've said elsewhere in this blog I didn't much like mmy dad. His faith scared me. But I am now just a few pages into this collection of letters, which span the time from late April 1976 when he first arrived in Minatitlan, Vera Cruz, Mexico until his death in October of that year, that he was undergoing a tremendous change which I have no doubt would have laid a foundation for reconciliation between the two of us.

But that's the least of it. A deeper pain is journalistic in nature. I feel that dread one feels when tackling a big, difficult but important and exciting story. The pain is more accute here because I am attached to it at the onset. But more signiificantly because it is shapping up to be a project unlike any I've ever taken on. So much of the story telling will be what I bring to it, and less what the story brings to itself, as is the case with most journalism. The structure is far froom obvious, and I tend to agonize when I don't have a fairly clear vision of where I'm going at the commencement.

Deepest pain of all comes in the aspect of discovery that is bound in this project, that I am not only going to unearth a story but that I am going to find aspects of myself, ugly ones, and that the project itself is a vehicle for self-discovery and change. All journalism projects are this way to a degree, but obviously this is a higher notch. Especially because this deals with issues of faith, spiritually and a sense of purpose in life and family and nation. I am at a stage of intense spiritual transformation, due to a number of factors I could name here but which I fear would be redundant and self serving. The main point is that I'm reading a historical record of the process of a spiritual transformation in a young man who was a lot like me, from whom I come, and in this reading come very difficult challenges to my own ways of being and assumptions and so on.

This, from a letter to Nan and Jim dated Friday, May 6, 1976, struck me:

For the first time I'm beginning to really like prayer and worship. Maybe that is not exactly true. But I have picked up a new perspective llately. It's so evident in the churches I visit what their worship is like. You can tell where a church is at from how they sing their songs and how they pray. It's a spiritual thermometer. Not only is it a thermometer but it is actually when the church really receives life from Christ. So long I didn't see it. All I saw was my own ministry or the church structure and so many times when there was worship I was nervous and anxious to get on to the "real thing," the thing that had substance. But now as I get closer to my ministry I'm beginning to see it has no substance at all to it. "We have all been unprofitable serveants." The real substance is fellowship with Christ. Nothing else really counts, not my church structure, not my ministry. If God takes us and uses us for silly looking things and forms of siilly looking structures out of our churches it doesn't matter. I can see that only in this light and perspective can the Kingdom of God be really shared and we can really be obedient. Otherwise other things can become our Lord. How ironic it can be.

I read this and regretted the post I wrote yesterday about Zion Chapel. I regretted my reaction to the service, my walking out and hoofing back to town on a country road. I regret too my propensity to criticize and preach. Over the last year it seems I've been apologizing a lot over outbursts of hot-headedness and self-riighteousnness.

Also, it's obvous here how simiilar I am to my father. He's clearly alluding to past conflicts he's had with his church, his judgement of how they choose to worship. I will probably learn more about the specifics of these co\onflicts in the coming years. But foo\r now I can see that if my dad had not died there would have been a moment, or moments of reconciliation where he would have realized how overzealous he was in his faith and how it really frightened me as a young child and messed up my own relationship with and understanding of God for many years to come.

This is a letter he wrote to me three days later:

Dear Joe,

How are you? I hope O.K. Last week i got a little sick for one day, but I am alright now.

Thursday I went to a small village with Miguel [the pastor he was working with]. The village has a church made out of boards from a palm tree. One side is curved and the other is straight. The roof is made out of leaves.

Anyway it is too small now and they wanted to build another church building, so we went there to start the new building. Miguel preached.

I am always amazed at how poor the people are. They have dirt floors and animals come in and out all day long. We were sitting in the living room and a pig walked right in the front door and out the back door. The place we ate didn't have a stove. They had a metal table with a camp fire on it, but there was no chimney, so the smoke went out through the palm leaf roof.

After lunch, we went to sleep for a while, then we went to the well, where the people get their water. They don't have sinks where the water comes up, so everyone has to walk a quarter mile outside the village to the well. The well is just a hole in the ground where the water comes up. All day long, people come to the well to get water in buckets, and they carry it home. Some dads send their kids to get the water. They ride down on burros with 2 water buckets on their burro in front of them. They get the water and then take it home to their houses.

Later in the day Miguel preached and then we ate and went home. It was very interesting. The neat thing is that people are happy here. They aren't sad because they doon't have electricity or water or cars or floors and a lot of other things.

I hoope that you write to me soon oor at least send me a few pictures. Also tell Grandpa to take a pictuure of you with the camera and send it.

Love,

Dad.

I cavalierly say that I didn't like my dad, but I really loved him. I especially loved his inate sense of the surreal, his childlike wonderment at the absurdity of the world. This letter touches me. I can almost remember feeling tickled when I read it, or my grandma read it to me, with the image of the pig just waltzing in. It's great writing, really; so simple and clean that it's downright subversive. It was addressed to a middle-class kid in the Midwest, who assumes that things like solid roofs and floors and straight walls are the norm for the entire world. To learn that there is something different actually made the priviliged norms of my world seem absurd.

I will share more by and by

funeral

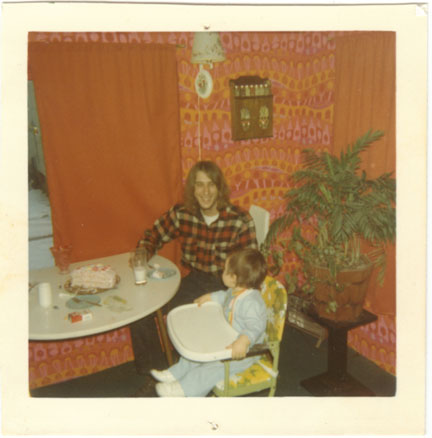

These were the pictures I really wanted. The one above is stunning. Toward the front are my grandfather and uncle Pete. Their hands are not raised to the spirit of the Lord. They are miserable.

My uncle Pete is on the left here, talking to my uncle Evan and Evan's wife, Gwen. To me, this picture sums up the year's between 1968 and 1976, not only for my family, but for America, part of it anyway.

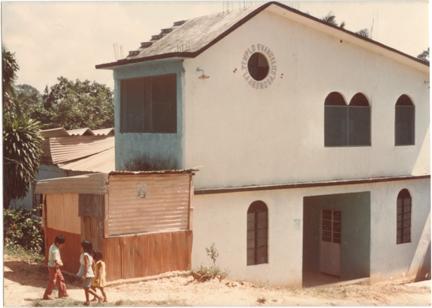

The church where my dad lived and died in Minatitlan, Vera Cruz, Mexico. His room was on the second floor, behind the big window.

The grave site of Carl S. Miller, Jr., my father.

From an earlier post on this blog:

After touring southern Mexico my friend dropped me off in Minatitlan, Vera Cruz, where my father is buried, and God spoke to me there. His words were clear, though not verbal, and they convinced me that Christ is my true salvation. Within a couple years I didn't believe any more.

While roaming the Mexican countryside with my friend, stopping to gaze at ruins and nudist beaches and jungle trees with spindly orchids clutching their bark, I'd thought long and hard about sacrifice. I was newly born again, the story of the crucifixion fresh in my mind. It was comforting to know that God would so love me that he'd stuff himself into a body like mine and offer his hands out to have nails driven through them. "Know" isn't the right word, really; I didn't actually believe it, not in the way that I believe that my cat is lying on my desk right now or that the sun rises in the east. I was 24 years old at the time, and in those 24 years I'd never known a person who was God compacted into flesh. So I simply couldn't believe, in the way I could never believe a person possesses the power of hurricanes or can drool fresh tomato juice. There's just no precedence on which to hang such beliefs.

But I believe in stories, the messages they convey, and the message of this God-As-Man-Dying-God-Awful-Death was one I liked, at least at the time, because I was young and lonely and I wanted to know that, if nothing else, God loves me.

Yet my tour of Mayan ruins obscured the free-pass notion of Christ, had shattered its simplicity. I'd heard the old "Why does God let bad things happen to good people?" discussion before. But this notion of sacrifice, in all its uncensored gore, was a lot to absorb. Particularly in Mexico, where injustices are stark, where my father fell to his death when he was just 27 years old. During my stay in Minatitlan I traveled with my hosts to a small village an hour or so inland from the Gulf of Mexico. It was just a cluster of cement homes, each smaller than a one-car garage, with corrugated tin roofs. There was a tiny clinic there, a government operation bearing posters with Spanish words that reminded people how to wash their hands and where to go to the bathroom and what shots their children should receive. It had a small cabinet full of medicine, and the place was very clean. The man who worked there, a nurse, had yellow eyes and he kept licking his lips because his mouth was very dry. I talked with him for a while, asking him questions in rugged Spanish, and he answered proudly, as though his clinic was a beacon of health. I assumed he had a terrible disease; he was so skinny and his eyes were yellow enough for a monster film. I didn't ask him about his eyes, though. I nodded a lot and smiled approvingly. He seemed happier than I. Everyone in the village seemed happier, even though the kids were all running around naked and the doors on the homes had no doors and the windows no glass and when it got dark it was black dark because most of the homes had no electricity and a canopy of palms blotted out the moon. I thought that I would die if I had to live there, in such a happy place.

My father's death hurt my grandparents deeply. Even all these years later, nearly two decades at the time of my Mexican tour, they would weep if they thought of him too much. My grandpa would say, Sons are supposed to bury their fathers, not the other way around. My dad was his first son. I was eight years old when it happened. I cried when I heard the news, of course, and I cried harder when I saw him in his casket, all bruised up at the front of a humid church, with a blob of slimy green preservative oozing out of his mouth. But it was easy for me to move on. He'd left my mother and I when I was barely two. We'd detached before we could form a solid bond. By my early twenties I could revisit his death as a third-party observer, study it like a story, something in the public domain from which to derive a theme.

The story as I was rewriting it was simple, a cliched drama of good arrising from bad: A young man goes off to serve God and dies young. His death leaves an aching hole in his family, one that can never be filled because the hole was there before he died. These were the seventies. My grandparents' children, three boys, were on the final stages of their runs through an America that had gone crazy. My father was the first one out of the gate. He got my mom pregnant while they were in high school, in the late 1960s. They married, and I was born, and my mom put up a picket fence. My dad rolled a joint, then another, then he dropped some acid and then he was gone, driving across the West in a pickup with an absurd, homemade camper sitting cockeyed in the bed. Along the way he got another woman pregnant, ditched her and then lost his mind. Family legend has it that he came home, got a job on some sort of farm and, one day, while his mind seethed with voices, he sprinted back and forth across a cornfield and cried to God: If You can make this stop I'll devote my life to You! He joined a church, one that was too conservative even for my grandparents' taste, and he was off again, in El Salvador and Nicaragua and Honduras and, finally, Mexico, to serve the Lord. Then he fell through a roof and landed head first on a concrete floor.

Then Good came. My grandparents started carrying on my father's work in Mexico. They bought a large for the preacher my dad worked with. They helped pay for the construction of a Bible school in a nearby town, which my father dreamt of doing before he died. They took many trips to Mexico, always to Minatitlan, a homely and hot PeMex town thick with oil industry waste, and these trips made their faith in Jesus stronger.

And there I was, by myself, at 24, newly reborn, thinking about all this. The questions spun: Are those villagers better for being desperately poor? Are my grandparents better off for having their son die? Are his brothers? Are the people in Mexico? The pastor's family? The people, God knows how many, who attended the Bible college? Am I? Did my dad die so that sixteen years later I would come to Mexico to hear The Story in just the right way, while I was in just the right funk, and be saved?

I sat by his graveside. His was a cheap headstone, made of cement, with his name and dates painted on it in a black paint that was starting to fade. My eyes scanned the words and numbers for several minutes before they registered. He died in October, 1976, I noticed, on the same day that I would, twelve years later, quit drinking and using drugs. I was 20 years old in 1988. One night after a relatively light guzzling of booze and smoking of pot, all alone, I was suddenly seized from my sleep. It was as though a firm hand had reached out of the darkness, yanked me up and slapped me on the face. Though it was two or three in the morning, I wasn't groggy: my mind was clear. I had three choices: quit partying, check into an insane asylum, or kill myself. The third option was the surest bet. I lived then in a place with high rafters, and I pictured myself tossing a rope over one and looping it around my neck. The ease of this scared the hell out of me, and I prayed then, though I didn't really believe in God. I said, If You help me get back to sleep, I promise I will stop partying tomorrow. I picked up a copy of the newspaper and read a story about the cook in the county jail. I was asleep before I reached the end.

In the back of my mind, I had long believed, unreasonably, I admit, that my father had yanked me out of bed that night. It's not unusual to believe such things, that deceased loved ones look over us. And, unlike the notion of Men Who Are Really God, there's enough precedence to give such believe credence: people receive messages from lost loved ones all the time, and they're relatively credible, though they could just as easily be written off as coincidence.

So I was thinking about all this at my father's graveside, marveling at the coincidence of the numbers -- same date, 12 years apart, one year for each step in the program I'd joined to quit drinks and drugs -- when all of a sudden I noticed a tree growing out of the side of my dad's grave. It was sort of a jungle cemetery, stuff was growing wildly all over the place, and it's easy to understand why I'd not noticed it. But my awareness was so immediate, and, coming as it did just as I was marveling at the numerology of my dad's death and the commencement of my sobriety, it was as if the tree had grown at that very moment, like one of those miracles in the Bible, like God's answer to all those questions that were spinning through my head.

I wandered back to the place where I was staying, where one of the pastor's kids was talking on the phone. She and I had plans to attend a movie in town. I wanted to tell her about my graveside experience, to ask if she thought it was a miracle, a message from God. While she talked on the phone, she handed me a greeting card that was sitting on the desk. It was a sappy religious card, the kind I wouldn't ordinarily give a second thought, with a misty photo of a baby under the caption, in Spanish: Because your father in heaven is watching over you. And I sunk back in my chair. All doubt disappeared. I was, in that moment, an avowed Christian with unshakable faith. God had spoken to me, three times, and told me it's true, true, true.

This sort of testimony is the stuff of Christian book store anthologies, where folks from North Carolina and Rhode Island write about how their lives were altered in a moment, and they've never gone back. But my faith began decaying almost immediately. Within a couple of years, I would barely believe in God, much less the story of Him coming to earth as a man to show that He cares about every little thing I do.

Friday, May 20, 2005

art, bitches

On Thursday, I took Ebony, Geoffery and Leodis to the Nelson and Kemper art museums on a whim. Initially, they weren't thrilled with the idea. "We're hetero," Geoffery said.

We went to the Kemper first, because I knew that one is free. As we strode up to the front door, I challenged them to find one piece of art that they like and to say why they like it.

Geooffery came back pretty quickly. He liked this:

It's by Naomi Fisher and it's called, "You Know That It’s Real If You Feel That It’s Real." Geoffery said he liked it because it said "Revolutution!" The fact that she's holding a machette instead of a sword appealed to him. Ebony and Geoffery too.

Ebony and Leodis liked this one, also by Fisher:

My favorite was a painting by Hung Liu, though not this one:

The one I liked showed a monochromatic image of a poor man and woman leading a horse. Overlaying their images were images of ancient Chinese culture, which were colorful and nooble looking. The painting was called "Passage" and I thought it was about oppression.

Geoffery is really into challenging my rhetoric aboout oppression and liberation. His latest rap is that people will always be oppressed. The world needs winners and losers. That's what makes life interesting. "You can't have Foucauult and Freire in the same realm," he said.

"Wait a minute," I said, reaching into my very limted understanding of these matters. "Foucault believed that liberation can occur through micropolitical movements. Yeah, the overall oppressive state structure will remain, but power can be shifted away froom it to the the oppressed through local action. And Freire provides a mechanism for that."

I think I beat him on the point, but he just shifted into a more ornery level of rightwing ideology, because he hadn't raised his first point so much out of conviction as to challenge me. That's Geoffery's thing. He likes to rile adults, pop their bubbles. That's what makes him a great debater and cool teenager.

What I like most about the exchange was that it was very loud, and everyone else in the museum could hear it. And I felt like we were subverting stereotypes, becaus folks don't usually expect teens in school uniforms to just start popping off about Foucault.

Then we went to the nelson (where the above photo was taken). We spent most of our time in the Asian wing. I learned a lot from the guys about Chinese culture, because both Ebony and Geoffery have been to China, and because Leodis is fascinated by Eastern culture and he reads a lot about it. We did make it to the 19th Century American painting section, and Ebony was really taken by the Thomas Hart Benton paintings, especially the ones where the figures are really curvy and colorful.

But all of the guys were taken by the curvy and colorful figures that were strolling around the galleries. As is usually the case, most of the museum goers were women. "See," I said, after we left the museum and they were drooling over the ogling sessiion they'd had, "art is totally hetero."

We went to the Kemper first, because I knew that one is free. As we strode up to the front door, I challenged them to find one piece of art that they like and to say why they like it.

Geooffery came back pretty quickly. He liked this:

It's by Naomi Fisher and it's called, "You Know That It’s Real If You Feel That It’s Real." Geoffery said he liked it because it said "Revolutution!" The fact that she's holding a machette instead of a sword appealed to him. Ebony and Geoffery too.

Ebony and Leodis liked this one, also by Fisher:

My favorite was a painting by Hung Liu, though not this one:

The one I liked showed a monochromatic image of a poor man and woman leading a horse. Overlaying their images were images of ancient Chinese culture, which were colorful and nooble looking. The painting was called "Passage" and I thought it was about oppression.

Geoffery is really into challenging my rhetoric aboout oppression and liberation. His latest rap is that people will always be oppressed. The world needs winners and losers. That's what makes life interesting. "You can't have Foucauult and Freire in the same realm," he said.

"Wait a minute," I said, reaching into my very limted understanding of these matters. "Foucault believed that liberation can occur through micropolitical movements. Yeah, the overall oppressive state structure will remain, but power can be shifted away froom it to the the oppressed through local action. And Freire provides a mechanism for that."

I think I beat him on the point, but he just shifted into a more ornery level of rightwing ideology, because he hadn't raised his first point so much out of conviction as to challenge me. That's Geoffery's thing. He likes to rile adults, pop their bubbles. That's what makes him a great debater and cool teenager.

What I like most about the exchange was that it was very loud, and everyone else in the museum could hear it. And I felt like we were subverting stereotypes, becaus folks don't usually expect teens in school uniforms to just start popping off about Foucault.

Then we went to the nelson (where the above photo was taken). We spent most of our time in the Asian wing. I learned a lot from the guys about Chinese culture, because both Ebony and Geoffery have been to China, and because Leodis is fascinated by Eastern culture and he reads a lot about it. We did make it to the 19th Century American painting section, and Ebony was really taken by the Thomas Hart Benton paintings, especially the ones where the figures are really curvy and colorful.

But all of the guys were taken by the curvy and colorful figures that were strolling around the galleries. As is usually the case, most of the museum goers were women. "See," I said, after we left the museum and they were drooling over the ogling sessiion they'd had, "art is totally hetero."

bible

The other day, I visited a longtime friend of my dad's named Bill Kambs. He gave me my dad's Bible.

It's a paperback that has been reinforced on the front and back cover with sturdy cardboard and duct tape. Its cover is made of really soft leather that my dad sewed together. Examining the cover, I noticed red drawings on the inside. They were little kid drawings of crosses and such. I took off the cover and turned it inside out. I think that this was the original cover, and that I drew the pictures when I was small.

What really makes this Bible a treasure is that my dad marked it up. There are many passages that he underlined very neatly, with a fine Rapidigraph pen and a ruler. It is priceless to be able to see which parts struck my dad and inspired him to underline so carefully.

Last night I started reading Matthew. I have never read the New Testament all the way through, much less the entire Bible. On several occasions I have set off to read the New Testament, because it seems an impoortant thing to read, whether you're Christian or not. But I can't recall ever getting much past chapter seven. I get through the sermon on the mount, and my mind is so blown -- or I'm so intimidated -- that I can't go on.

Jesus was a tough son of a, um, God. I read it and I think, How on earth can anyone be a fundamentalist? This time I read it and I became convinced that I will never believe that anyone is a fundamentalist until I meet a person with one eye and one hand.

I had hoped to discover that my dad had underlined my favorite passage:

(He underlined this last sentence.)

(Actually, when I really think about this, I have to say that birds do sow, reap and gather.)

(I'm not convinced that I am, but go on.)

(Bingo! Now I'm hooked. But my dad didn't underline this.)

(Here my dad starts underlining again, in green pencil, for the big payoff, the "what you should do" part, the praxis.)

Makes it all sound so easy, and I feel comfort in it, I guess becauuse it says, basically, Dude! Look at nature. Everything's gonna be alright. Just do your part.

But then, it's the "do your part" part that's a trip. If my part is what Jesus laid out on the mount, I'm fucked. We all are. He says to do the most radical stuff: tear out your eye if you're horny; cut off your hand if it makes you stumble; if someone sues you, giive them everything (hello Mr. President! tort reform?); get beat up; go the extra mile; love enemies and pray for them; if you get mad then you're guilty of murder; pray in secret; give charity so secretly that even half of yourself doesn't know the good things you've done; don't pray with meaningless repetition; forgive everybody no matter what mean, wrongheaded stuff they do to you; don't collect material treasures; don't judge anybody; enter the narrow gate, not the nice big one, and walk the narrow path, not the wide one, where hardly anyone else is.

He wraps it up in a no-nonsense way:

(Which I have a hard time reconciling with this Born Again stuff, like: All we have to do is say "Jesus is Lord" and we're cool, our tickets to heaven will be waiting at the Will Call window.)

Now, when I read this, my first thought is George W. Bush is going to hell. But then I'm like, we all are. How can anybody live up to this stuff?

I know I haven't read the whole book. I'm probably taking it all out of context. There's probably a part in the next chapter or so where Jesus says, "I was just kidding. Just say you believe in me, and you can do whatever you want, except have abortions and gay sex, and you'll be free and clear in heaven. A'ight!"

I wonder what my dad would think of Bush and megachurches and all this stuff that, from my perspective, doesn't seem to gibe with Jesus at all.

It's a paperback that has been reinforced on the front and back cover with sturdy cardboard and duct tape. Its cover is made of really soft leather that my dad sewed together. Examining the cover, I noticed red drawings on the inside. They were little kid drawings of crosses and such. I took off the cover and turned it inside out. I think that this was the original cover, and that I drew the pictures when I was small.

What really makes this Bible a treasure is that my dad marked it up. There are many passages that he underlined very neatly, with a fine Rapidigraph pen and a ruler. It is priceless to be able to see which parts struck my dad and inspired him to underline so carefully.

Last night I started reading Matthew. I have never read the New Testament all the way through, much less the entire Bible. On several occasions I have set off to read the New Testament, because it seems an impoortant thing to read, whether you're Christian or not. But I can't recall ever getting much past chapter seven. I get through the sermon on the mount, and my mind is so blown -- or I'm so intimidated -- that I can't go on.

Jesus was a tough son of a, um, God. I read it and I think, How on earth can anyone be a fundamentalist? This time I read it and I became convinced that I will never believe that anyone is a fundamentalist until I meet a person with one eye and one hand.

I had hoped to discover that my dad had underlined my favorite passage:

No one can serve two masters; for either he will hate the one and love the other, or he will hold to one and despise the other. You cannot serve God and Mammon.

(He underlined this last sentence.)

For this reason I say to you, do not be anxious for your life, as to what you shall eat, or what you shall drink; not for your body, as to what you shall put on. Is not life more than food, and the body than clothing?

Look at the birds of the air, that they do not sow, neither do they reap, nor gather into barns,

(Actually, when I really think about this, I have to say that birds do sow, reap and gather.)

and yet your heavenly father feeds them. Are you not worth much more than they?

(I'm not convinced that I am, but go on.)

And which of you by being anxious can add a single cubit to his life's span?

(Bingo! Now I'm hooked. But my dad didn't underline this.)

And why are you anxious about clothing? Observe how the lillies of the field grow; they do not toil nor do they spin, yet I say to you that even Solomon in all his glory did not clothe himself like one of these.

But if God arrays the grass of the field, which is alive today and tomorrow is thrown into the furnace, will he not much more do so for you, O men of little faith.

Do not be anxious then, saying "What shall we eat?" or "What shall we drink?" or "With what shall we clothe ourselves?"

(Here my dad starts underlining again, in green pencil, for the big payoff, the "what you should do" part, the praxis.)

For all these things the Gentiles eagerly seek; for your heavenly Father knows that you need all these things. But seek yee first His kingdom and His righteousness; and all these things shall be added to you.

Therefore do not be anxious for tomorrow; for tomorrow will care for itself. Each day has enough trouble of its own.

Makes it all sound so easy, and I feel comfort in it, I guess becauuse it says, basically, Dude! Look at nature. Everything's gonna be alright. Just do your part.

But then, it's the "do your part" part that's a trip. If my part is what Jesus laid out on the mount, I'm fucked. We all are. He says to do the most radical stuff: tear out your eye if you're horny; cut off your hand if it makes you stumble; if someone sues you, giive them everything (hello Mr. President! tort reform?); get beat up; go the extra mile; love enemies and pray for them; if you get mad then you're guilty of murder; pray in secret; give charity so secretly that even half of yourself doesn't know the good things you've done; don't pray with meaningless repetition; forgive everybody no matter what mean, wrongheaded stuff they do to you; don't collect material treasures; don't judge anybody; enter the narrow gate, not the nice big one, and walk the narrow path, not the wide one, where hardly anyone else is.

He wraps it up in a no-nonsense way:

Not everyone who says to Me, "Lord, Lord" will enter the kingdom of heaven; but he who doesthe will of My Father who is in heaven.

(Which I have a hard time reconciling with this Born Again stuff, like: All we have to do is say "Jesus is Lord" and we're cool, our tickets to heaven will be waiting at the Will Call window.)

Many will say to Me on that day, "Lord, Lord, did we not prophesy in Your name, and in Yourname cast out demons, and in Your name perform many miracles?"

And then I will declare to them, "I never knew you; DEPART FROM ME, YOU WHO PRACTICE LAWLESS."

Now, when I read this, my first thought is George W. Bush is going to hell. But then I'm like, we all are. How can anybody live up to this stuff?

I know I haven't read the whole book. I'm probably taking it all out of context. There's probably a part in the next chapter or so where Jesus says, "I was just kidding. Just say you believe in me, and you can do whatever you want, except have abortions and gay sex, and you'll be free and clear in heaven. A'ight!"

I wonder what my dad would think of Bush and megachurches and all this stuff that, from my perspective, doesn't seem to gibe with Jesus at all.

Thursday, May 19, 2005

nuts

I am not an expert on Michel Foucault. I probably do not understand him in any meaningful way. I started but did not finish Discipline and Punish and Madness and Society. The former begins with a gruesome acount of a public execution where a a man is publicly beaten, burned and torn apart in most vicious way. At the end of this unusually gripping lead to an academic text, Foucault says something about punishing people beyond pain. Honestly, I'm not sure exactly what he said, and the book is all the way upstairs, but the sense I got was that the punishment was more for the punisher than the punished. And in the book about madness, Foucault suggested, at least in the early parts I read, that the insane are an other that we seek to repel, to lock away, but by whom we are also defined.

I have probably got this all wrong. I feel as though I need to really study Foucault's work. There is so much to know.

I have probably got this all wrong. I feel as though I need to really study Foucault's work. There is so much to know.

fire

I recently downloaded an RSS feed reader, and I compulsively loaded it with sites to scan. Now, every time I turn the damn thing on, several times a day, I have several hundred news articles waiting for me. I don't find it liberating. I find it to be oppressive and disturbing. It's like playing a jackpot machine. What am I looking for? Why is so much of this stuff the same? Why do all political stories seem to fall under pretty much the same framework? If several times a day we learn from Fark that some one has done something unusual with a goat or a duck can it continue to be unusual? Do unusual things not happen in our own lives? Do people really like Wonkette? I don't. Why has everyone except for one bright blogger from St. Louis said pretty much the same, short-sighted stuff about the Newsweek situation? What's the point of all this crap? And why am I contributing to it? Is this a conversation? If I write a story and it's distributed to X readers, what is the point of that story? I am reading 1984. Newsfire reminds me of the Ministry of Truth where Winston Smith worked.

Recently, I watched a documentary about Jacque Derrida. In it, he quoted Heideger (I think) about Aristotle's (I think) life: "'He was born, he thought and he died.' And anything else is just anecdote." Then Derrida said that perhaps the best or truest biographer is one who takes a very small passage from a person's body of work and interprets that rigorously and deeply. There was another scene where he shows the film makers his library. It is full of books. Derrida admitted he had not read all of them. Just three or four, he joked. "But I read those very well."

But then, what could be more powerful than anecdote? I feel as though I am living a story, as I believe all humans do. And it is this sense of narrative, I think, which potentially binds us, which possibly melts away difference. The playwrite Terrence wrote is one of his plays: "I am human, therefore nothing human is foreign to me." And this is one of my favorite quotes (though when I first learned of it, in college, I was mistakenly told that it came from Mircea Eliade, whose work I should probably read. Which is why I'm a journalist, I suppose. I want to find that connection.

But still, why so much? And why be drawn to such a repellent fire of over saturation? Allie and I sometimes joke that we'll stay on the Internet long past the time we'd really like to, racking our brains to come up with search terms which might lead us to something interesting. It's really a frustrating place to be, because it can be so difficult to find it. Indeed, the stuff that really rocks us has been your traditional substantive media, books, documentaries, quality movies.

So I wonder if all this proliferation of media isn't really just more of the same: Not much different from a greater and greater consolodation of information because in the fragmentation it really ceases to matter and it pulls us away from the things that would, which require much more investment of time and effort. I wonder if amid so much information we're actually getting less. Or, at very least, if that information is actually disempowering us.

Indeed, the most interesting thing I read on my NewsBonFire was a bit about how the more we know the stupider we get. With so much information to juggle,m we are forced to categorize more and more, and, from what I've read recently, categorization is a concept that's batted around quite a bit by psychologists, and that it has quite a bit to do with our inate, or supposedly inate, prejudices and bigotry (KCC debate evidence).

But then, what else are we going to do? So long as it's there, can we really expect ourselves not to take a peek? And then another peek? And then another? After all, if I hadn't looked in the fire, I wouldn't have found that piece about thinking, which will probably stick with me for a long, long time.

Recently, I watched a documentary about Jacque Derrida. In it, he quoted Heideger (I think) about Aristotle's (I think) life: "'He was born, he thought and he died.' And anything else is just anecdote." Then Derrida said that perhaps the best or truest biographer is one who takes a very small passage from a person's body of work and interprets that rigorously and deeply. There was another scene where he shows the film makers his library. It is full of books. Derrida admitted he had not read all of them. Just three or four, he joked. "But I read those very well."

But then, what could be more powerful than anecdote? I feel as though I am living a story, as I believe all humans do. And it is this sense of narrative, I think, which potentially binds us, which possibly melts away difference. The playwrite Terrence wrote is one of his plays: "I am human, therefore nothing human is foreign to me." And this is one of my favorite quotes (though when I first learned of it, in college, I was mistakenly told that it came from Mircea Eliade, whose work I should probably read. Which is why I'm a journalist, I suppose. I want to find that connection.

But still, why so much? And why be drawn to such a repellent fire of over saturation? Allie and I sometimes joke that we'll stay on the Internet long past the time we'd really like to, racking our brains to come up with search terms which might lead us to something interesting. It's really a frustrating place to be, because it can be so difficult to find it. Indeed, the stuff that really rocks us has been your traditional substantive media, books, documentaries, quality movies.

So I wonder if all this proliferation of media isn't really just more of the same: Not much different from a greater and greater consolodation of information because in the fragmentation it really ceases to matter and it pulls us away from the things that would, which require much more investment of time and effort. I wonder if amid so much information we're actually getting less. Or, at very least, if that information is actually disempowering us.

Indeed, the most interesting thing I read on my NewsBonFire was a bit about how the more we know the stupider we get. With so much information to juggle,m we are forced to categorize more and more, and, from what I've read recently, categorization is a concept that's batted around quite a bit by psychologists, and that it has quite a bit to do with our inate, or supposedly inate, prejudices and bigotry (KCC debate evidence).

But then, what else are we going to do? So long as it's there, can we really expect ourselves not to take a peek? And then another peek? And then another? After all, if I hadn't looked in the fire, I wouldn't have found that piece about thinking, which will probably stick with me for a long, long time.

Wednesday, May 18, 2005

Tuesday, May 17, 2005

the soles of gray folks

I've been wearing Crocs ever since I bought them (for $25). Don't matter where. Garden. Grocery store. Disco.